Being A Mark That Can Be Erased To Be Unnamed

15 Bytes Magazine. Drawings by John Sproul and poems by Lynn Kilpatrick by Geoff Wichert

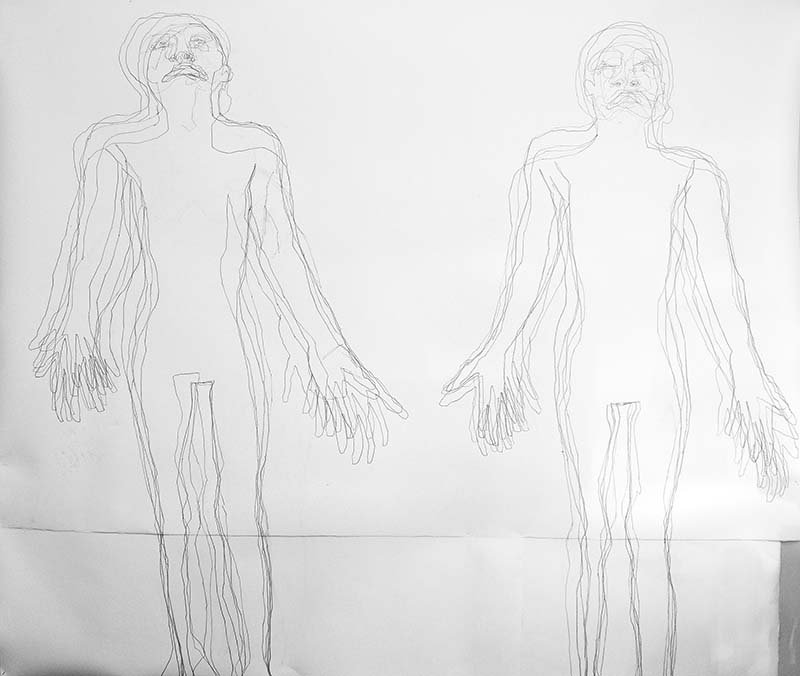

Art doesn’t ask questions: people do. So when Salt Lake Community College professor Lynn Kilpatrick first saw the ‘blind’ drawings by John Sproul that form the visual half of their joint show at the City Library, questions came to mind as part of her response. Fortunately, Kilpatrick is among the more original writers on the literary scene today, so her questions, and the stories that emerged with them from her imagination, eventually became a remarkable collaboration of art and prose poetry. Those who come and stand before To Be Unnamed will almost certainly ask questions of their own. For instance, we know that when the words come first, the pictures are illustrations. When the images come first, the words that follow are captions. Neither of these terms seem to fit here, so what are we looking at?

For those who haven’t seen it yet, there are two structural devices in To Be Unnamed. The works come in pairs, each containing one elaborate drawing and one prose poem inspired by the drawing. The poems are also related to each other, united in their own thematic structure. Called a crown of sonnets, the series calls for the last line of one sonnet to become the first line of the next, and so on around the entire ‘crown.’ Since nothing literal connects each pair, it falls to the poet’s intuition to forge a metaphorical unity, which she has done. Unfortunately, as noted elsewhere, Sproul’s and Kilpatrick’s combined visions exceeded the space available in the Library. The complete work had to be hung out of the intended order, so the effect is imperfectly realized here. Nevertheless, while author and artist invite us to look back and forth, seeking connections, we can and should also view the parts of each pair separately, as well as seeing each together with the others of its kind.

When drawing, an artist’s eye usually moves back and forth, from the original model to the copy, optically measuring the one and transferring those dimensions onto the other. In so-called ‘blind drawing,’ the eye remains fixed on the model, and the artist’s brain relies on kinesthetic sense—the dead reckoning of the joints and muscles—to capture angles and distances. Thus, seen dimensions are translated into felt dimensions, a process analogous to the internal process by which objective, factual experience is given subjective, emotional expression: not what happened, but how it made you feel. Where academic training seeks to remove subjectivity from the process, in favor of accurate reproduction of specific, visible facts, blind drawing abandons those details in favor of the visual and anatomical equivalents known to all of us. Even beginners can produce drawings that, despite some inaccuracy, bear an uncanny resemblance to the subject, and the eerie overall effect can be satisfying to someone who is struggling to produce any effect at all.

To Be Unnamed.

Blind contour is usually an artistic dead end, unable to transcend its accidental effects. But in To Be Unnamed, John Sproul breaks through such limits, harnessing its well-known characteristics to expressive purposes by tracing the same subject, the same contours, over and again, as closely as possible, in the same place. Sometimes he separates successive drawings with layers of translucent gesso. At others he produces nearly concentric figures that vibrate nervously, seem to approach and withdraw, or vie with each other over which will dominate the optical impression. While a healthy sense of humor is evident, and despite its mundane history, Sproul’s process roots itself in serious art, and in particular in cubism: in the desire to capture not only distance, but time as well in a single drawing. Yet where the cubist artist moved around the object of his attention, encoding its multiple perspectives into a single image and thereby rendering it monumental, Sproul sits still, animating and energizing his image —sometimes until it shatters. The result has a cinematic quality, but in reverse: in a film, the persistence of vision creates the illusion of continuous existence out of a sequence of still images. Here, a continuous, potentially narrative existence is broken down into a seeming sequence of no-longer cohesive moments: instantaneous states of mind, vital energy, or awareness crystallized in pixillated snapshots. In place of greater or lesser visual accuracy, Sproul proposes fidelity to what is only guessed at by the eye.

And then Lynn Kilpatrick responds, sometimes with abstract musing —“The way a language dies is not only unbreathed, but unthought,” she says in “I’m not sure she” —while in “One Man Out” she speaks for the artist:

This is progress. Things move in the right direction. People begin to understand. One thing represents one other thing. Black equals one idea. White another. The line demonstrates the thingness of the universe. One thing can represent another thing. Not always the thing we seek to represent. What if the eye I speak does not blink? What if the ear does not receive? Will you know the hand with its four fingers? Say you will understand the symbol I set out for you. Say you will enter with me into the ratio of one to one.

The Woman I Once Knew But Can’t Remember

Where a sonnet would have fourteen lines, “One Man Out” has fourteen sentences. Like all the poems in To Be Unnamed, it is unrhymed and its meter prosaic. Its sentences vary in length. Each poem in the crown takes a title from the drawing it accompanies: “Something Something Blah,” “The Woman I Once Knew But Can’t Remember,” “Where Do I Go Hear?” The closing line of each poem becomes the first line of the next poem, leading the reader and viewer around the work. The poet’s reflections on the goals and limits of art are sometimes expressed in terms of the artist’s struggle, at other times the poet’s. Sometimes they merge: is “a line” something that is drawn, or something that is spoken?

Yet here, as in her richly praised collection of short pieces, In The House, Kilpatrick reveals more universal concerns, including—but not limited to—the difficulty of communication, the hazards of connection, the ease with which meaning goes accidentally astray, and the impossibility of making intimacy last. Her perspective acquires a greater dimension from Sproul’s masculinity; when he draws a woman, Kilpatrick honors his priority. On the other hand, she indulges a strong trend in recent literature toward recognition and inclusion of demotic texts: lists, instructions, notes, sketches, and other mundane reasons for writing lend their shapes to works traditionally created to fit more refined structures, which are now replaced by forms that ground the writing in quotidian reality. It might even be argued that in To Be Unnamed, she has added captions to the list of transformed reasons for writing.

It begins with three figures unmoored on a large expanse of white. Sproul has drawn each four or five times, and the writer has chosen to acknowledge these facts of the drawing, reading them in several successive ways. “You improvise something like a dance,” she says of their cartoon-like motion. “You cannot contain even yourself,” she remarks of colliding boundaries, even as “Your soul moves outside your body in a smudge meant to convey meaning, passion, desire.” Consider: “There are more than two of you, more than three. This sentence is not you, nor this. Nor this.” Who, standing here, doesn’t know that feeling?

One of the things writers can do is lie to us, and because their lies are written down, they can be very effective. Freud said we forget our traumas, and for a century that was gospel, in spite of its being obvious that the worse an experience is, the more we must try yet the harder it is to forget. More recently, a popular myth has been that language is a poor tool, that weak and clumsy words cannot express our most important or subtle thoughts. Or we may say that only a Dante or a Shakespeare can make a word do a task well. Kilpatrick, in her elevation of everyday uses of language, proves that even the most mundane act of speech can not only capture, but reconfigure material facts. “Oh, to be you. That’s what you say. To be myself and to know myself as a mark that can be erased.” Is that the drawing speaking? A mark that can be erased? Or is it the artist, whose work might be his immortality? Or isn’t it, finally, each of us . . . a disruption of the pattern that engulfs us, into which we will inevitably dissipate, what remains too faint to perceive?

It is we who are poorly equipped for our self-appointed tasks. We are fragile, easily broken and usually misunderstood. Language, both in words and in drawings, can not only make us coherent, but through it we reach out in space and time. Evidence is at hand that proves the point.

To Be Unnamed: Blind Drawings by John Sproul and poems by Lynn Kilpatrick is at The Gallery at Library Square, on the fourth floor of the Salt Lake City Main Library, through June 14. Lynn Kilpatrick's In The House is available from Fiction Collective 2. You can view more of John Sproul's work at johnsproul.com.